by Gabrielle Pepin

Policy Recommendations

-

States wishing to extend Child and Dependent Care Credit (CDCC) benefits to low-income families should offer refundable credits that are a function of the “allowable” federal CDCC.

-

A promising strategy to maintain quality standards is to condition CDCC benefits on state-administered quality ratings of child care providers.

Child and elder care in the United States is notoriously expensive. For instance, in recent years, the average household with children in the bottom fourth of the income distribution spent nearly 20 percent of their income on child care alone (Herbst 2018). Researchers have found that these costs keep many caregivers from working, as they would easily eat up a good chunk of take-home pay (Averett, Peters, and Waldman 1997; Guner, Kaygusuz, and Ventura 2020; Michalopoulos, Robins, and Garfinkel 1992; Miller and Mumford 2015; Pepin 2020). Although many policymakers continue to recommend policies designed to promote employment opportunities, income support for child and elder care at the federal level remains quite limited. If states and localities wish to create shared prosperity and to help their residents get and keep good jobs, they should thus act independently to reduce care costs.

Some states already provide a road map: supplements to the federal child and dependent care credit (CDCC). When states supplement the federal CDCC, residents get an additional tax credit based on their income and care expenses, effectively lowering their out-of-pocket costs. Because the credit is tied to work, it also encourages labor force participation. Moreover, my research suggests well-designed state CDCCs can increase work and earnings while transferring income toward parents and caregivers.

How Does the CDCC Work?

The federal CDCC is available to all working families with children younger than 13 or with a coresident spouse or dependent “physically or mentally incapable of self-care.” To qualify for benefits, all nondisabled taxpayers in the household must have positive annual earnings, including both spouses among taxpayers married filing jointly. Households meeting this work requirement may claim up to $3,000 in care expenses for each of up to two qualifying individuals, receiving a nonrefundable tax credit worth up to 35 percent of those expenses, or $1,050. However, benefits begin to decrease once household adjusted gross income (AGI) reaches $15,000, plateauing at $600 per qualifying individual once AGI exceeds $43,000.

Expenses eligible under the credit include fees paid to child and adult daycare facilities, family child care homes, and attendants assisting dependents with activities of daily living. Claiming the credit requires filling out Form 2441 on the household’s tax return, reporting expenditures and the care provider’s tax identification number.

The federal CDCC is not as generous as it may seem, however. The federal credit is nonrefundable, which means that it can only offset income taxes owed—low-income working households who owe no income taxes do not receive benefits. This stands in stark contrast to other refundable tax credits targeted at working families, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, for which households may receive a tax refund.

In practice, this limitation is a big deal. For instance, a one-parent household with two children and $15,000 in annual earnings has no federal income tax liability and therefore will not receive any federal CDCC benefits, regardless of how much they spend on child care. Meanwhile, a two-parent household with two children and $50,000 in annual earnings may receive up to a $1,200 credit each year. In my research, I find that nearly one-quarter of one-parent households who work and pay for child care have incomes too low to receive benefits. As these households are disproportionately Black and Hispanic, nonrefundability perpetuates both income and racial inequality.

How Can State CDCCs Reduce Care Costs?

Twenty-two states offer their own state child care credits that are directly tied to the federal CDCC. Additionally, Idaho, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, Virginia, and Wisconsin offer individual income tax deductions for child care expenses. (Deductions lower taxable income while credits offset taxes owed.) Colorado, Iowa, New Mexico, Oregon, and the District of Columbia offer child care credits that are not a percentage of the federal CDCC or the expenses used to calculate it. In most cases, these state benefits are just a fraction of the federal credit. However, unlike the federal CDCC, some states offer refundable credits, limit benefits to taxpayers with incomes below a certain threshold, or provide larger benefits to low-income households.

For example, Maine and Delaware each provide a state care credit equal to half of the federal credit, without refundability. Thus, the hypothetical one-parent household with two children and $15,000 in earnings receives no care credits in these states because its income was too low to get any federal credit. In contrast, California and Louisiana offer CDCCs worth up to $1,050, half of the $2,100 in federal benefits the household would receive if the federal CDCC were refundable. California’s CDCC is itself nonrefundable, though, so the hypothetical household with $15,000 in earnings, which does not have state income tax liability, still receives no benefits. Only in Louisiana, which offers a refundable CDCC based on the allowable federal credit, may the household receive up to $1,050 in state CDCC benefits.

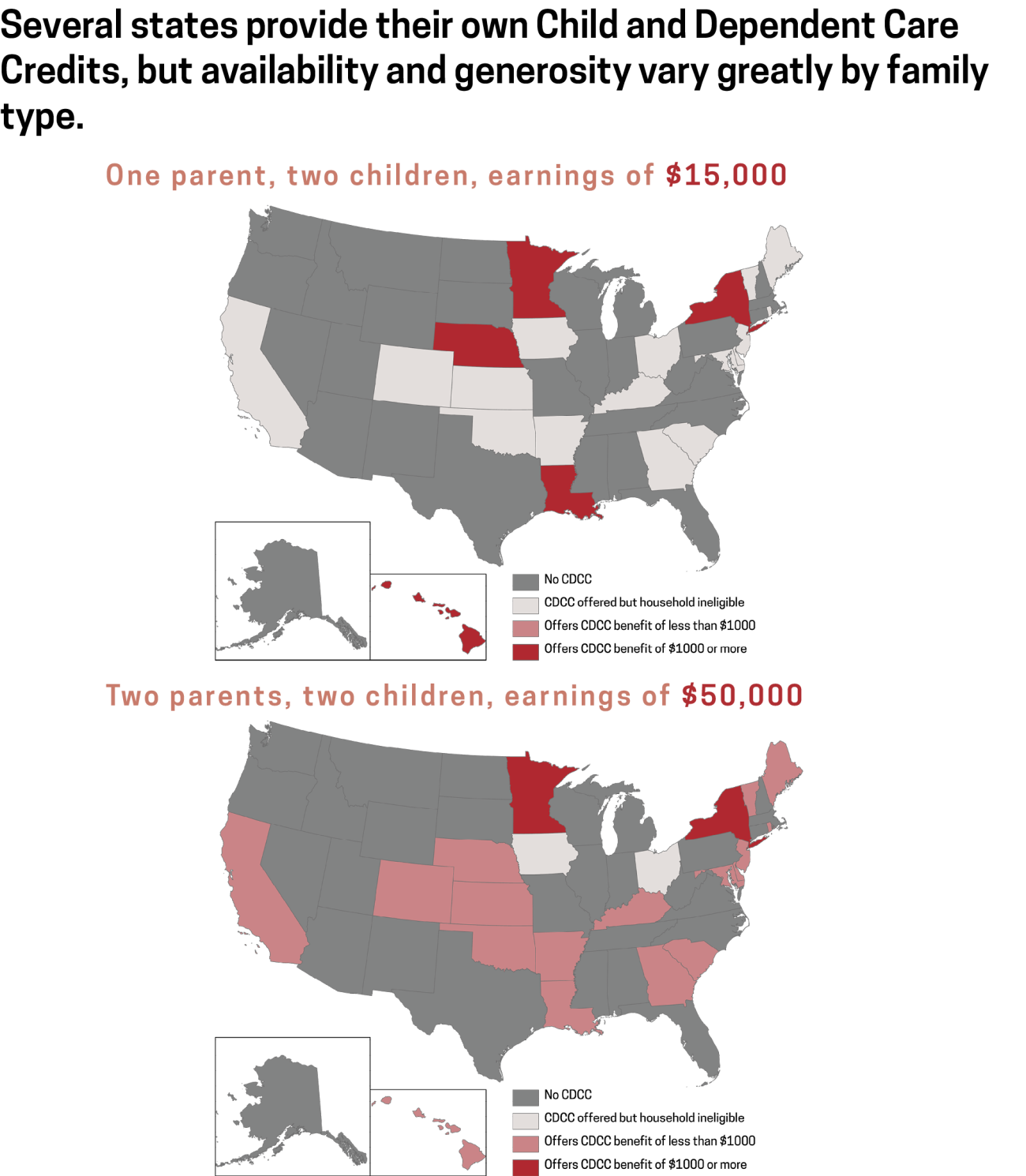

The effectiveness, or “take-home,” of state CDCC benefits can vary by place and income. For example, single-parent families with two children, $15,000 in earnings, and no additional income are unlikely to have access to state CDCC benefits. Among the five states that do offer benefits to these households, however, state benefits top out at over $1,000 per year.

On the other hand, two-parent families with two children and $50,000 in earnings are much more likely to have access to state CDCCs. Twenty states offer these households benefits, with maximum benefits ranging from $120 to $2,100 annually.

How Can States Help to Ensure Care Quality?

One concern about the CDCC is that it may lead to reduced care quality if it encourages households to pay for low-quality care instead of providing higher-quality care themselves. This concern is valid: the quality of child care affects children’s development and long-term outcomes (Cornelissen et al. 2018; Cunha and Heckman 2007; Havnes and Mogstad 2011). To help alleviate concerns about care quality, a few states tie their CDCCs to state-administered ratings of provider quality. For example, for the single-parent, low-income family, maximum benefits in Louisiana increase with the rating of child care provider, from $1,050 at any provider up to $5,250 at providers assigned the highest possible five-star rating.

Conditioning the amount of the state CDCC on state-administered quality ratings is appealing because it creates an incentive for high-quality care without requiring new bureaucracy: 40 states and the District of Columbia already administer Quality Rating and Improvement Systems to assess early care and education programs’ quality levels. Parents can access these ratings and other provider information online, allowing them to see how choosing different providers would affect the size of their CDCCs. Although these quality rankings tend to exist only for child care providers, states could extend the rating systems for care providers serving adults with disabilities.

Conclusion

States can supplement the federal CDCC with their own credits to lower residents’ out-of-pocket care costs while encouraging work. For state CDCCs to be effective labor market policies, however, they must reach their targeted beneficiaries. To reach low-income families, states should thus offer refundable care credits tied to the federal CDCC. Making the size of these state credits more generous at higher-rated care providers may help ensure care quality.

References

Averett, Susan L., H. Elizabeth Peters, and Donald M. Waldman. 1997. “Tax Credits, Labor Supply, and Child Care.” Review of Economics and Statistics 79(1): 125–135.

Cornelissen, Thomas, Christian Dustmann, Anna Raute, and Uta Schönberg. 2018. “Estimating Marginal Returns to Early Child Care Attendance.” Journal of Labor Economics 126(6): 2356–2409.

Cunha, Flavio, and James Heckman. 2007. “The Technology of Skill Formation.” American Economic Review 97(2): 31–47.

Guner, Nezih, Remzi Kaygusuz, and Gustavo Ventura. 2020. “Child-Related Transfers, Household Labor Supply and Welfare.” Review of Economic Studies 87(5): 2290–2321.

Havnes, Trajei, and Magne Mogstad. 2011. “Subsidized Child Care and Children’s Long-Run Outcomes.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3(2): 97–129.

Herbst, Chris M. 2018. “The Rising Cost of Child Care in the United States: A Reassessment of the Evidence.” Economics of Education Review 64: 13–30.

Michalopoulos, Charles, Philip K. Robins, and Irwin Garfinkel. 1992. “A Structural Model of Labor Supply and Child Care Demand.” Journal of Human Resources 27(1): 166–203.

Miller, Benjamin M., and Kevin J. Mumford. 2015. “The Salience of Complex Tax Changes: Evidence from the Child and Dependent Care Credit Expansion.” National Tax Journal 68(3): 477–510.

Pepin, Gabrielle. 2020. “The Effects of Child Care Subsidies on Paid Child Care Participation and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from the Child and Dependent Care Credit.” Upjohn Institute Working Paper No. 20-311. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.